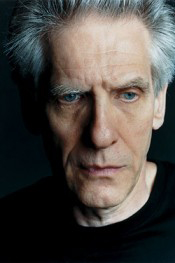

Each of director David Cronenberg’s movies are a new journey for him as a filmmaker, just as they are for us as an audience. “It’s all intuitive. It’s all creative. I have no agenda,” Cronenberg said. “When I came to do A Dangerous Method, it’s as though I’d never made another movie.” He’s referring to his latest film, which transports us to Zurich and Vienna on the eve of the First World War. There we find Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) at the start of his career, as he attempts Sigmund Freud’s (Viggo Mortensen) experimental treatment called psychoanalysis on a young woman named Sabrina Spielrein (Keira Knightley). A breakthrough is made and they become pioneers in their field, but at a high cost. Infidelity occurs, friendships are tested and lives are changed forever in this multi-layered story of lust, love and the challenge to face our true selves. Cronenberg and I talked about psychoanalysis, the allure of filming in Europe, Knightley’s preparation for her role and more.

What originally attracted you to this story, which began in Zurich, Switzerland in 1904?

The richness of the characters and the era. The birth of psychoanalysis in central Europe just before World War 1. The texture of the times – it’s just fascinating stuff and these were just fascinating characters.

Your film Crash inspired a great deal of controversy because of its subject matter – people who derive sexual pleasure from car accidents. Sex has been a driving force in many of your films, including A Dangerous Method.

Sex is a huge motivation for all kinds of activities in human life. This is one of things that Freud insisted. The reality was that he was talking about it at a time when the whole idea of sexuality was very repressed. It was what we would call a Victorian era in Vienna in the early 1900s. Freud was insisting on the importance of sex as a motivation for all kinds of things as a human drive. So for a filmmaker, it’s a no-brainer. As George Bernard Shaw said, “Conflict is the essence of drama.” Nobody wants to see a movie where everything is nice. So drama involves conflict and conflict involves drive whether it’s physical or psychological. Sexuality is a huge drive in human beings. I think it’s inevitable that movies deal with sex on some level or another. That’s not unique to me at all. I wish I could take credit for it. Sex and death are pretty big topics and the Greeks did it 3,000 years ago.

Your last three films, A History of Violence, Eastern Promises and A Dangerous Method represent a departure from your earlier horror work. What inspired the switch?

Sure my first three or four movies were horror films that I wrote myself, but people forget that I also did a drag racing movie called Fast Company. I think people’s perception of what I do is actually quite distorted. They don’t really get the whole picture and they conveniently leave things out because they have affection for the horror films. People remember when they were ten years old when they saw Scanners and they kind of want to relive that. But for me, there’s no switch. It’s all the same. There’s no difference. Each movie makes its own demands. For example, A Dangerous Method is not the first film I’ve done that’s a period piece. Naked Lunch, M. Butterfly and Spider were all set in different times. Obviously, each film is a different project, but it’s all one piece to me creatively.

Jung and Freud, two men who are masters of the mind, are both attracted and influenced by Sabina. Is sex more powerful than people think?

You see in the movie that sex was a major topic. At a certain point, it was a divisive force between Freud and Jung. Not physically in their emotional lives, but theoretically. Freud was giving full weight to the importance of human sexuality at a time when people were trying to repress that and not talk or think about it. That was hugely important. At the beginning, Jung was buying into Freud’s theories of the repression of sexuality being the main cause of neurosis and mental illness. Later, Jung began to think that it was a simplification and that sex couldn’t be everything that Freud was saying it was. It couldn’t be the only cause. It couldn’t be the only problem. At a certain point, they sort of parted ways philosophically. Jung seized to be a pupil of Freud’s and went off to develop his own quite different theories of mental illness and psychoanalysis.

At a certain point in their lives, do you think there was a sense of competition between Freud and Jung?

Freud was very upfront about his relationship with Jung and vice versa because that was the stuff of psychoanalysis. You do not keep anything under the covers. They knew that they were living out a sort of father-son relationship both personally and professionally. As Freud pointed out with the Oedipus complex, that relationship does involve a certain amount of competition automatically. And even though there is love between father and son, there is somewhere the desire for the son to destroy the father in order to come into the light himself. So all of this is Freudian theory and all of this was being lived out by Freud and Jung. That is one of the beauties of the structure of this movie.

Keira Knightley’s performance was powerful. As a director, did you let her go at any point?

No, it was all discussed in great detail. The symptoms of Sabina Spielrein were very well known because we have Jung’s analysis of her. In his own handwriting, he details her symptoms. In the movie, we are creating an accurate portrayal of Sabina’s suffering from hysteria, which was a very particular disease at the time of mental illness. It was considered primarily to be a disease of women. The word hysteria comes from the Greek word that means uterus. They would actually remove the uteruses of women to cure them of the disease, which is a pretty hideous thing when you come to think of it. Also, there are photos from the famous French psychiatrist Charcot who was one of the mentors of Freud. He specialized in hysteria and took photos and film footage of his patients, which you can see. So however extreme you might think what Keira is doing at the beginning of the movie, it is absolutely accurate in terms of what hysteria was – this sort of distorting and deforming of your face. When you think of it, she’s trying to speak things for a woman of that time and social class that were unspeakable. She’s saying that she’s sexually aroused by her father beating her. This was unacceptable. So she’s trying to say it, but she’s trying to not say it at the same time. Keira’s performance came out of long discussion and study. The way that she prepares for a role is fantastic.

A lot of letters were going back and forth between Freud and Jung in the film.

It was an era of letter writing. These people were very obsessive about recording everything as well. That was in the nature of psychoanalysis. You record your dream in great detail. You record your erotic experience in great detail. You didn’t cover up anything. You didn’t hide anything. And you were excruciatingly honest about all of your feelings. We have all of these letters. Sabina’s were discovered only in 1977. She was an unknown figure before that. They were discovered at the University of Geneva in a suitcase where she had left it when she left to go to Russia. Those letters unleashed a huge barrage of academic study of Sabina and her importance to psychoanalysis, which had not been known before. In that suitcase were letters from her to Freud to Jung and back and forth. Once again, incredibly detailed and we could see that she was a huge influence on their thinking. And she was absolutely their intellectual equal as well.

You have set your last two films in Europe. Why is it attractive to you for storytelling?

As a filmmaker, you feel that you will go wherever the story leads you. If it leads you into Russia, then you’ll go to Russia. If it leads you into Asia, then you’ll go to Asia. The excitement about being a storyteller is that there are no boundaries. I don’t feel bound to one city or one town. I feel that the world is my oyster.